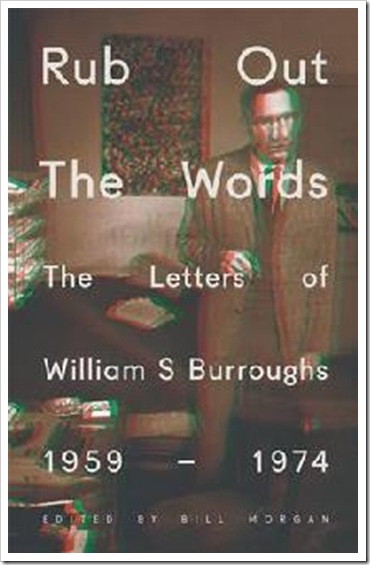

Rub Out the Words: The Letters of William Burroughs 1959-1974, επ. έκδ. Bill Morgan, (Penguin Hardback Classics)

Γράφει ο James Campbell | Guardian,

Friday 23 March 2012 »»

Ο δεύτερος τόμος με τις επιστολές του Μπάροουζ.

Με τον τόμο αυτόν καλύπτεται χρονολογικά η περίοδος από την έκδοση του Naked Lunch το 1959 έως το 1974.

William Burroughs was so far out he practically wasn't here at all. "I hope I have made myself clear," he wrote to his friend and collaborator Brion Gysin in August 1969, "and repeat that by the fact of being here we are not in control and that is what the war is about, the control of our inner space." Burroughs treated the popular libertarian ideas of the time with contempt – "the 'new freedom' and the 'permissive society'" – as he did the propaganda of militant groups such as the Black Panthers. Eldridge Cleaver had urged white comrades to arm themselves, he told Gysin. "Well, I can do more for any revolution sitting at this typewriter than I could plinking around the streets with a Beretta 25."

Just when you feel inclined to agree, the cosmonaut of inner space takes a further turn: "The weapon to use is mass control of brainwaves. 400,000 brains in one spot emitting alpha waves of sleep and dream could dream the fuzz away and, if they want it the hard way, 400,000 epileptic waves makes an electric fence."

Rub Out the Words is the second volume of Burroughs's letters. The first, published in 1993, covered the early Beat Generation days in New York, the composition of Naked Lunch in Tangier, and the obsessive, unrequited love for Allen Ginsberg. It left the lonely traveller in the Beat Hotel in Paris, with a series of books being published to little notice by the Olympia Press.

Now Burroughs is in London (8 Duke Street, St James, Mayfair; time for a plaque, surely), experimenting with cut-ups, fold-in texts, spliced tapes, collage photographs and other technical adventures. Burroughs's idea was that hidden meanings and foretellings were released when segments of different text or tape were alchemised by these means. A hex could be put on enemies, friends' ill-fortune prevented. He was interested not so much in literary artefacts – though even the cut-up novels, The Ticket that Exploded and The Soft Machine, make good reading if taken in small doses – as in shaking off malign agents of control.

Following a lengthy explanation to Gysin, by far his main correspondent, of how to influence fate by doctoring film, he warns that their foes will "never allow anyone to leave this planet … If we don't win we won't be able to leave." At the same time, Burroughs is kind to people in need, and frequently solicitous of information about his troubled son, Billy, who had been left in the care of Burroughs's parents in Florida: "I am convinced that Billy's difficulty and the difficulty of many young people today arrives from the fact that he does not have anything to do."

A phrase that has no place in Rub Out the Words is "Beat Generation". Exploring inner space, Burroughs had left the Beats behind. In a letter to Ginsberg at the close of the earlier volume, he had hinted at a "new method of writing", but told his friend to expect nothing more: "I cannot explain this method to you until you have had the necessary training."

Ginsberg is regularly patronised here. Gregory Corso is "marked lousiest in my book … Piss Poor Player". Jack Kerouac is pitied for his alcoholism and mother dependency. When it comes to Herbert Huncke, the Times Square hustler sometimes ranked as the ur-Beat, Burroughs finds himself at a loss for words, reaching into the hoard and dredging up some Shakespeare instead (as he often does, Macbeth being a favourite): "He is not only a junkie and a thief, strong both against the deed in the words of the immortal bard the raven himself is harsh who croaks the fatal entrance of Huncke."

The main agent of control in Burroughs's life was the debilitating influence of narcotic drugs. What made him happy was work, particularly collaborative work, and heroin militated against the contentment of a day at the desk, pen in one hand, razor-blade for cut-ups in the other. A repetitive strain in Rub Out the Words concerns the apomorphine treatment pioneered by the London doctor John Yerbury Dent, in which Burroughs was a passionate believer. In letters to the press, to other doctors and to fellow addicts, he stressed that apomorphine "does not work by allaying anxiety but by regulating metabolisms so that the patient does not need alcohol or narcotics". That the various authorities ignored Dent's remedy came as no surprise; after all, as Burroughs put it in The Job, a collection of interviews published in 1969, doctors have a vested interest in ill-health. He was also a champion of Scientology, and urged Gysin and others to obtain e-meters for self-auditing on the way to becoming "clear".

The fact that London was the base of operations for most of the period covered by the letters – with frequent excursions to Tangier, New York and Florida – gives the volume added interest for British readers. Young men come and go at the Mayfair flat, combining domestic or secretarial duties with amorous companionship. Alexander Trocchi, an advocate of heroin use in a way Burroughs emphatically was not, was nevertheless "a great cat". Both were involved with the underground press – International Times, Rat, Moving Times – and planned to establish their own magazine, M O B (My Own Business). Relations with publishers were strained: John Calder, publisher of both Burroughs and Trocchi, "just can't bear to part with money"; Jonathan Cape, which issued two Burroughs titles, was astutely judged to be "trying to get a reputation for being avant-garde publishers without taking any of the risks involved". In Paris, Maurice Girodias of the Olympia Press swindled Burroughs out of thousands, but somehow retained his loyalty.

By 1972, however, he was getting fed up. "Power cuts here," he wrote to Billy, by then himself a novelist and drug addict (he died in 1981). "England is a gloomy, cold unlighted sinking ship that will disappear with a spectral cough." He told Calder he was planning to leave London: "I would appreciate any information you can give me about prices and living conditions in Scotland." By the spring of 1974, he was on his way, not to Edinburgh – "beautiful city" – but New York.

Rub Out the Words will be welcomed by Burroughs addicts everywhere. Readers apt to become queasy over droll routines that begin, "When asked about his final solution to the female problem Burroughs puffed thoughtfully at his Havana … Extermination is not the word", might prefer to seek their kicks elsewhere.

Unfortunately, the editing is atrocious. The first volume benefited from the expertise of the Burroughs scholar Oliver Harris. For this instalment, Bill Morgan has taken a scattergun approach to names and basic information on important characters such as Dr Dent, whose dates are omitted (1881-1962) and whose name is wrongly given as "John Yerby Dent". A cut-up of The Waste Land sent to Tambimuttu, the well-known editor of Poetry London, with the amusing recommendation, "As you know Mr Eliot has followed somewhat the same method", comes without illumination. What was it for? Was it used? Morgan can't even say where Tambimuttu was at the time, offering a feeble "[New York?]" instead. Adopting his severe-parent persona in 1964, Burroughs chided Gysin for a lazy communication: "No time is ever saved by doing something improperly. Any letter you write should be your best letter." The same goes for editing.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου